With the rapid depletion of IPv4 addresses, Network Address Translation (NAT) has become an essential component of modern networks. NAT allows multiple devices to share a single public IP address, enabling secure and efficient communication between private networks and the internet.

IPv4 came out in the early 1980s

The young Internet lived in a world of mainframes

-

Many user terminals leashed to one central machine on the Internet

-

Personal microcomputers in the first generation, few modems even

-

Internet backbone ran only to advanced research facilities

Only researchers really cared about Internet resources

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses: e.g., 134.10.2.45

- Surely 4.2B addresses are enough!

"I think there is a world market for maybe five computers." – surely apocryphal remark attributed to Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM

By the early 1990s, the Internet had grown up

Original assumptions of the Internet, defied

-

Now primarily a consumer tool, not a research tool

-

Internet became accessible through modems, then broadband and cellular

-

A clear path to billions of devices on the Internet

-

Devices are always on, always connected

-

No option other than increasing the address space

The IPng initiative

-

Undertaken by the IETF in the early 1990s (see RFC1550)

-

Led to IPv6 RFC1883 published in December 1995, mature version in RFC2460 December 1998 (What happened to IPv5, anyway? See ST-II RFC1819)

Virtues of IPv6

Plenty of addresses

-

340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,211,456

-

That’s 128 bits, 340 undecillion or 3.4×1038

-

Grouped into /64s, blocks of 18 quintillion addresses

-

IPv6 fixes the network prefix at 64 bits

-

Enough addresses in a network that they can be chosen whimsically

- 2001:19f0:feee::dead:beef:cafe (freenode)

- 2001:420:80:1:c:15c0:d06:f00d (cisco)

- 2620::1c18:0:face:b00c:0:1 (facebook)

IPsec built-in from the start

- Vint often remarks this was the greatest shortcoming of IPv4

However, a new standard can’t be introduced overnight

What’s the interim strategy?

Multiplexing an IP Address

IETF created “private” address space RFC1918 (1996)

-

Most famously 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, 192.168.0.0/16

-

Technically, the 172.16 block is 16 contiguous /16s, and the 192.168 block is 256 contiguous /24s

ip-masq in 1997

-

Allowed multiple computers to sit behind one modem’s Internet connection

-

Required application-layer gateway (ALG) for sophisticated features like FTP

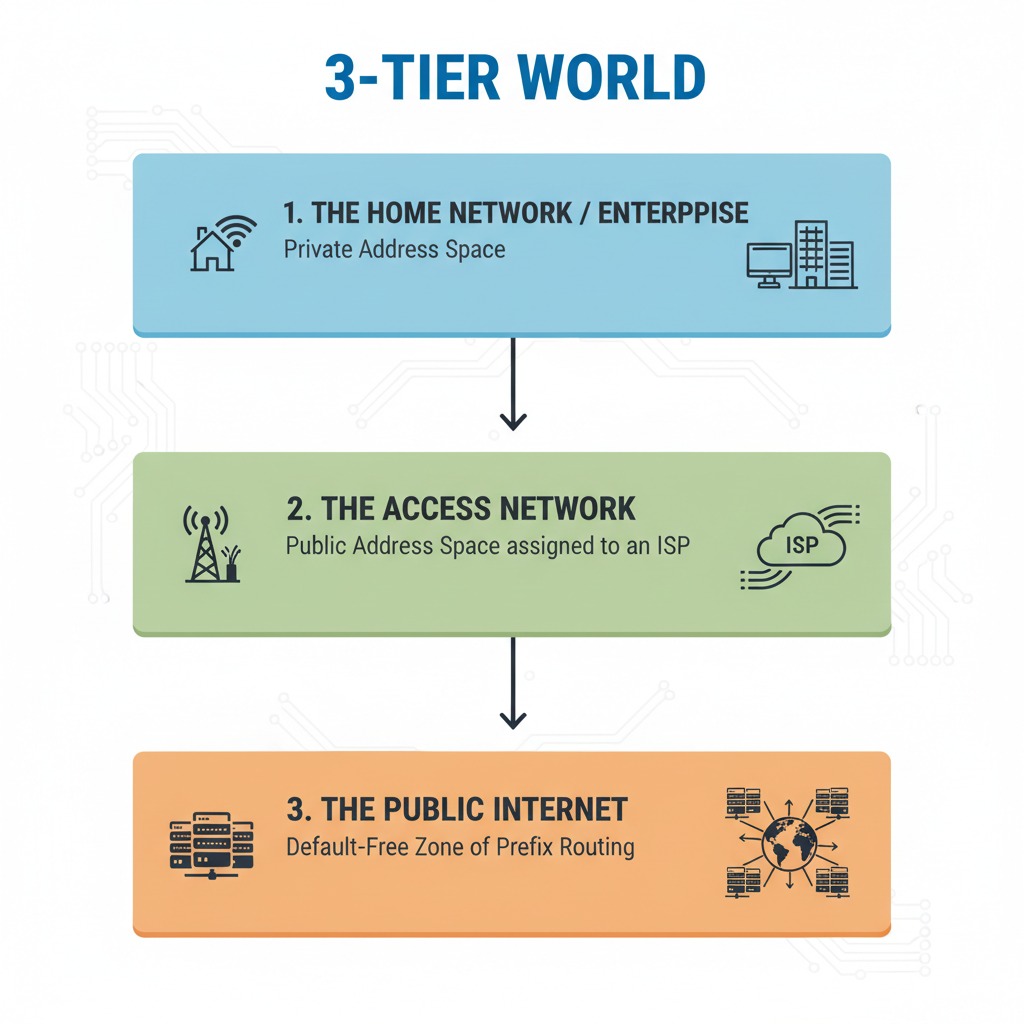

Today the ubiquitous home “router” is mostly a Network Address Translator (NAT)

-

Has one public IP address on the WAN side, maps external ports to internal

-

Private addresses served via DHCP on the WiFi/Ethernet side

-

Your computer’s IP address has a good chance of being 192.168.0.1

-

If you can’t reach DHCP, then link-local autoconfiguration (169.254.0.0/16) RFC3927

-

Implements various NAT, firewall and forwarding policies, supports many sorts of ALGs

The Dark Bargain of NAT

Work by masking the address from which packets are sent

-

The NAT effectively hides the addresses behind it

-

Effectively firewalls the private network

-

However, recipients can’t distinguish endpoints behind the NAT

NATs optimize for client-server connections

- Surfing, downloading, gaming

NATs interfere with asynchronous notifications

-

A NAT opens “pinholes” only when a client on the inside sends traffic out

-

When services on the outside want to send traffic in, you have a problem

NATs bungle rendez-vous protocols that require endpoints to know their own IP

-

A variety of workarounds have been developed to address this

-

These create real problems for peer-to-peer applications

- Skype and BitTorrent are triumphs of engineering

Ultimately, strict conservation and NATs merely delayed the inevitable

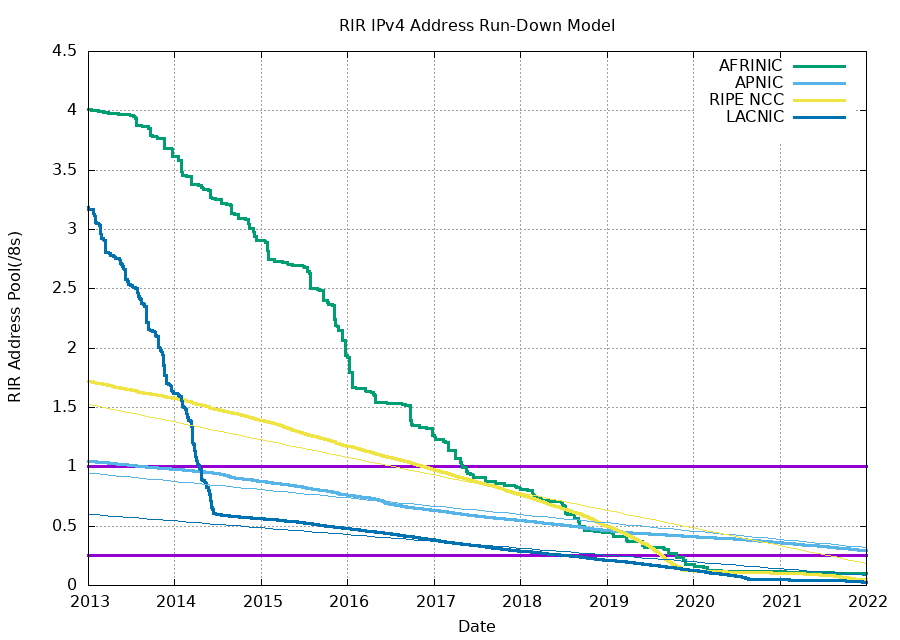

Final IPv4 IANA assignment rule invoked Feb 3 2011

-

At that time, the five remaining /8s held by IANA were allocated, one each, to the RIRs

-

As of April 2011, APNIC already ran out

-

RIPE ran out on September 14, 2012

-

The rest will follow in the next couple years

- Right now, ARIN & LACNIC have 3 /8s left, AFRINIC has 4